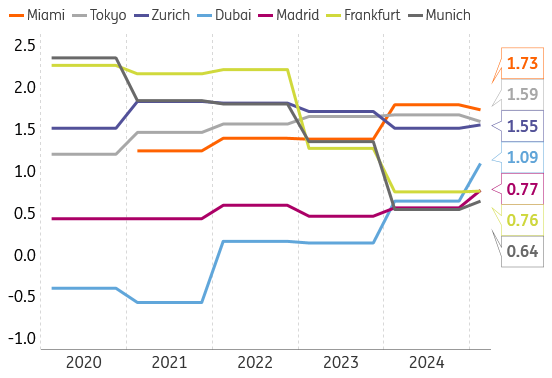

On September 23rd, Swiss bank UBS released its Global Real Estate Bubble Index 2025, an annual ranking that measures bubble risk in 21 major cities around the world.

This year, Madrid, alongside Dubai, has recorded the largest increase in housing bubble risk. The Spanish capital scored 0.77, which UBS classifies as moderate risk (a range between 0.5 and 1.0).

Globally, Miami tops the ranking with a score of 1.73, making it the city most at risk of a housing bubble. It is followed by Tokyo (1.59) and Zurich (1.55). Madrid sits in the middle of the pack, close to Frankfurt (0.76) and Munich (0.64).

What stands out most, however, is that Madrid leads real price growth among all cities analyzed, with home values rising 14% year-on-year.

UBS explains:

“Inflation-adjusted rents rose by about 10% over the past year, driven by new household formation and limited supply of new housing. Prices climbed even faster, nearly 15% in real terms, supported by foreign investor demand. Although lower mortgage rates could support local demand, price growth is likely to slow in the coming months.”

Price bubbles are a recurring phenomenon in property markets. Economically speaking, a “bubble” is a substantial and sustained mispricing that only becomes obvious once it bursts. Still, history offers a few warning signs that can help detect excesses before they explode: prices decoupling from incomes and rents, excessive credit expansion or a surge in construction activity.

According to the ECB’s RESV Index, which measures housing overvaluation relative to its “fundamental” value, prices in Spain are 14.3% above where they should be. More concerning still, the index rose 3% in a single quarter, the sharpest increase on record. The eurozone average stands at 10%, meaning Spain is diverging rapidly from the European trend.

Data from the Bank for International Settlements show that between late 2013 and early 2025, real housing prices in Spain jumped 45%. Yet they remain about 20% below their 2008 peak, when the last bubble burst.

In September 2025, the average price of existing homes, which make up most of the market, reached €2,517 per square meter, up 15.3% from a year earlier and a new nominal record. Adjusted for inflation, though, prices are still below pre-crisis levels.

All signs point to a market under pressure, but not in classic bubble territory. The real story lies in the supply-demand mismatch: unlike in 2008, when oversupply caused the collapse, Spain now faces a severe housing shortage.

The market remains in an expansion phase, fueled by lower interest rates, stronger purchasing power and solid economic growth. Demand continues to rise, supported by both domestic buyers and a steady inflow of foreign investors. Supply is recovering, but still far from bridging the housing gap accumulated since 2021.

Over the 12 months to June 2025, around 700,000 housing transactions were recorded in Spain, a 19.7% increase from the previous year and the highest level since 2007. But today’s context is very different: Spain now has 4.3 million more people and 3.2 million more households than back then. In other words, there are 14 transactions per 1,000 residents, compared with 17 in 2007, a sign that today’s demand reflects genuine household needs, not speculative frenzy.

Most sales involve existing homes, although new builds have gained slightly, rising from 21% in 2024 to 22.2% in early 2025. At the peak of the previous boom, that share was 42%, underscoring how far today’s market is from a construction glut.

Foreign buyers also remain a powerful force. In the first half of 2025, they purchased around 50,000 properties, representing 14% of total sales, well above the historical average of 10.5%. Their activity is concentrated in coastal and tourist regions, where price pressures are most intense.

Between 2021 and 2024, Spain created around 900,000 new households but built only 500,000 to 600,000 homes, a shortfall of roughly half a million to three-quarters of a million units, equal to about 4% of the country’s total housing stock. Put simply, for every five new households, only one new home was built.

As a result, many secondary homes, around 360,000, have been converted into primary residences, a temporary fix that is nearing its limits. The shortage is most severe in major urban and coastal areas like Madrid, Barcelona, Málaga, Alicante, and Valencia, where demand far outpaces supply.

According to CaixaBank Research, each additional percentage point of housing shortage pushes prices up by 0.6 points per year. Overall, supply shortages explain about 40% of Spain’s price increase since 2021.

So, is there a housing bubble in Spain? The data suggest no. This is not a cycle of excess but one of scarcity. The real risk is not that the bubble bursts, but that housing becomes structurally unaffordable if supply fails to catch up with demand.